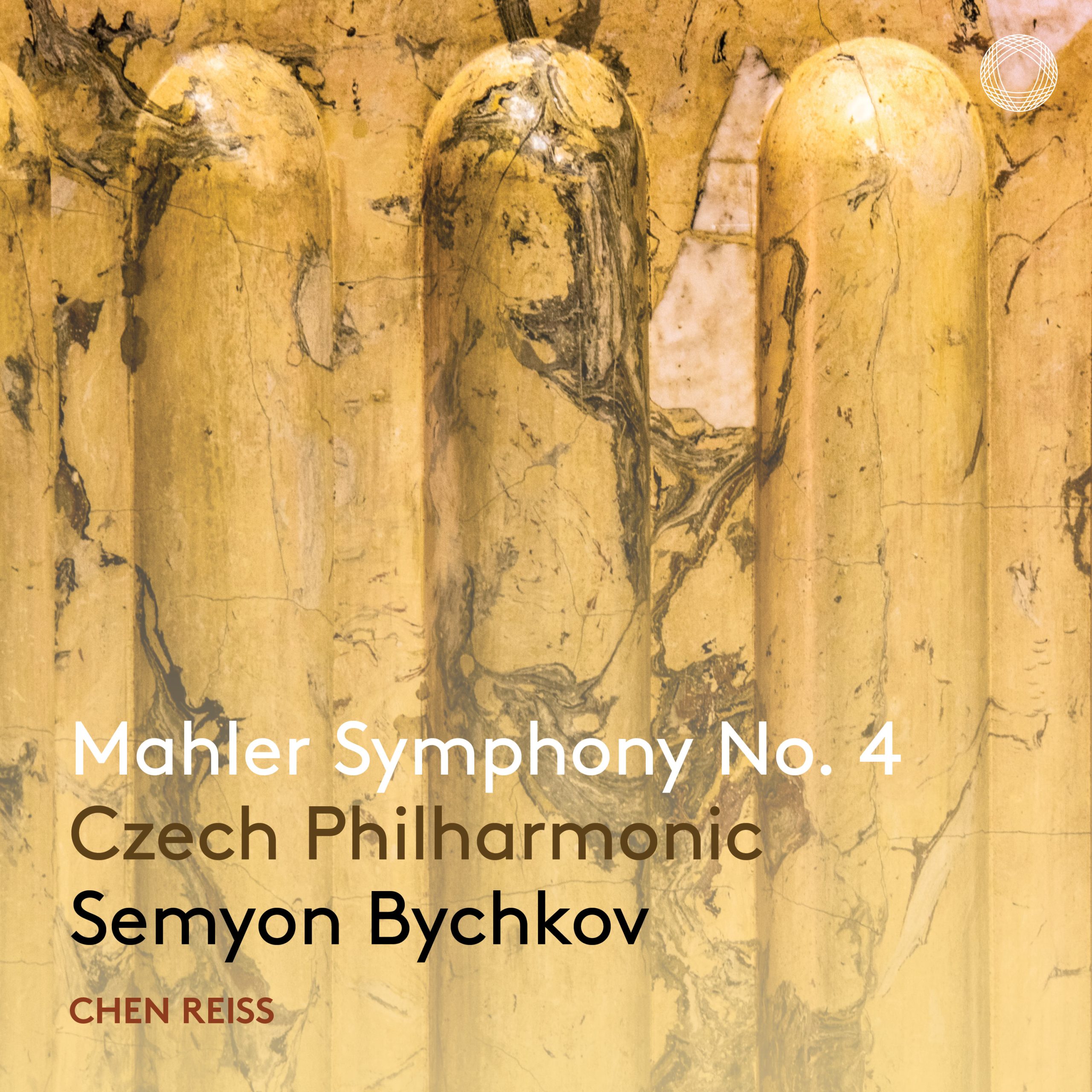

Chen Reiss Soprano

Czech Philharmonic Orchestra

Semyon Bychkov Conductor

Pentatone PTC5186972

Full price

The Review

There are performances where the conductor is barely discernable, where the music feels everyday and standard, its familiarity enough to make it presentable, the orchestra playing as they always do. Semyon Bychkov simply doesn’t allow that level of complacency, from orchestra or listener.

It is odd to put on a CD and be able to visualise each gesture from the man on the podium but Bychkov requires the placing of each note, each accent, with such particular care that Mahler’s tunefulness is never the point. Many other conductors, when they take such a detailed approach, can end up like clockmakers who have taken the great machine apart and mistaken the shiny cogs for the grandeur of the whole machine. Somehow Bychkov avoids that while pointing every entry from his players with fierce control.

To say this is a deeply thought-through performance really does not do the man justice. He interrogates the score with great affection but incisive care. Pianissimi are as quiet as possible without requiring ear strain, brass is brash and coarse if necessary, timpani strong and startling. This is often thought of as Mahler’s most jolly and uncomplicated symphony – and of course it is shorter than most – but Bychkov gives the lie to that. His reading constantly reminds us that, however pretty and untroubled the scenery, cruelty is always waiting in the wings. Perhaps because the second movement is so charming, the unease is unnerving. Such gorgeousness will soon be destroyed. Mahler’s own words, quoted in Gavin Plumley’s excellent liner note, almost say that. “It is only that it [the blue sky] seems suddenly sinister to us – just as on the most beautiful day, in a forest flooded by sunlight, we are often overcome by a shudder of dread panic.”

In the slow third movement Bychkov helps the players shape each sound so that it finds its home as if it had been teased into place with tweezers. If this sounds fussy, it is not. It forces the listener to pay attention and not take any phrase for granted. He often slows the tempo to a point where the wait for the next bar is agonising, yet the flow is not interrupted. The string sound is different in each movement too. At the start it is so unlike the usual Czech Phil, as if he has roughed up the sound with coarse sandpaper, especially the cellos, accentuating the danger and the folk origins of Mahler’s style. Then in the Adagio the ethereal unity of the violins reasserts itself but here he has clearly learnt from period practice. There is a lot of portamento but much less obvious vibrato than in most performances from the 1950s onwards. Where vibrato is allowed, it is deliberate, not automatic.

This has all the makings of becoming a classic recording. My one problem with it is that I cannot warm to the soprano in the last movement, Chen Reiss. Her diction is woolly and her tone lumpy and imprecise. She simply does not soar in a way that portrays heaven as the words demand. The archness should lend the poem from Das Knaben Wunderhorn a sense of irony (the second stanza is bloodthirsty in a way that undermines the thrust of the song) – the innocence might be skin deep – and Reiss just gives everything to us a straight: an ordinary day in the Dvorak Hall. Bychkov deserves a singer who can match his ability to convey the multiple meanings that make this symphony so universal – I kept wishing Lucia Popp was still with us. If Reiss is not perfect, though, the Czech Phil’s wind section is, so almost all is forgiven.

SM