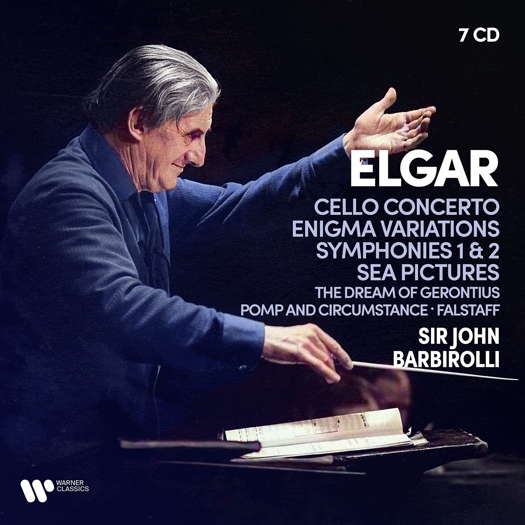

Sea Pictures

Serenade

Enigma Variations

Symphonies 1 & 2

Pomp and Circumstance Marches 1 – 5

Falstaff

The Dream of Gerontius

Cockaigne Overture

Froissart

Sospiri

Elegy

Dream Childen (Andante)

Lullaby

2 Arias from Caractacus

Jacqueline du Pré Cello

Janet Baker Mezzo

Richard Lewis Tenor

Peter Dawson Baritone

Kim Borg Bass

Ambrosian Singers

Sheffield Philharmonic Chorus

Philharmonia Orchestra

Hallé Orchestra and Choir

London Symphony Ochestra

Sinfonia of London

Sir John Barbirolli Conductor

Warner Classics 0190296438424

7 CDs

Budget Price

The Review

The immediate pleasure of opening this set is that the seven CDs are packaged with the iconic HMV sleeves that graced the original LPs from the 1960s, starting with the du Pré Cello Concerto and Dame Janet’s Sea Pictures – an album which no self-respecting music lover of my generation was without.

Somewhere I also have the much scratched LP that had the Enigma Variations and Cockaigne. Of course, the pieces here are from several other LPs too, quite simply because of the much longer scope of the CD (70+ minutes compared to 45). And what is listed on the front is not always what is contained on the disc, which is confusing for a moment or two. Falstaff, for example, is not on the CD with the Second Symphony (as on the cover of CD 4) but on CD 5 with Froissart and three of the Pomp and Circumstance Marches.

These are such beloved recordings that it is hard to listen to them dispassionately and perhaps there is no need to. Barbirolli was every bit as committed an Elgarian as Adrian Boult but Boult had the advantage of being ten years older and conducting for a further nine years after Barbirolli’s death at the age of 70, so has often been more associated with the works. Whereas Boult met Elgar socially in 1904 and started conducting his work almost as soon as he entered the profession, Barbirolli was a cellist first and played in the LSO at the unsatisfactory premiere of the Cello Concerto in 1919, which may well explain his rapport with the young du Pré for this recording forty-six years later. Importantly too, it was Elgar who encouraged him to become a conductor and he repaid the debt, not only with the British orchestras but in his years at the New York Philharmonic, a time when Elgar’s music was not heard anything like as much in the US as it had been in the early part of the century.

Generally Barbirolli’s readings of Elgar are gentler, more romantic, perhaps more Brahmsian, than many of the recordings of the first half of the 20th century, including Elgar’s own. He blends the orchestral textures in a mellow continuum, softening the more martial elements without blunting anything. The tunes are more important that the rhythmic punch. The result is that Elgar is freed from the pompous posture of Englishness and the music fits far more into the European mainstream. This is particularly telling in the two symphonies. The fact that Elgar played first violin under Dvorak (in what is now the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra), just as Barbirolli played cello under Elgar, makes sense of the approach.

More recent recordings find conductors divided between the two schools, Barbirolli’s somewhat steady but enveloping readings and what Elgar might have termed the fresh-air, more bracing, ones. I find I like veering from one to the other and back because each side of the music is valid. And in Sea Pictures no-one has ever bettered the combination of Dame Janet and Sir John. In the minor works, though (the Serenade for Strings, Sospiri, Elegy), and in the overtly rumbustious pieces (Pomp and Circumstance, Cockaigne) the romanticism feels a little too cinematic to my ears now.

For Gerontius (on two discs with a very short first one), Barbirolli probably had the best combination of singers ever assembled on record for the work. Richard Lewis has just the right combination of vocal strength and inner vulnerability. His tenor is never strained and is free of English cathedral boyishness without sounding like a Wagnerian heldentenor. Kim Borg as the Priest, despite a rather peculiar accent, has real bass authority. At almost 31, Janet Baker was just coming into her vocal prime and her Angel is the perfect counterweight to Lewis, with a tone that is so individual yet strangely androgenous. It strikes me that these days we would not be surprised to find it was a countertenor like Andreas Scholl. The three choir chorus is cleverly placed so that it is distant enough to be within reach, especially when being devilish, but sufficiently other worldly for us to realise that Gerontius is not among them yet. Where the interpretation really is brilliant is in the way Barbirolli does not over dramatise, avoids operatic melodarama and lets the music unfold with long lyrical lines. It becomes remarkably contemporary – not an end of the 19th century oratorio filled with Catholic religiosity by a deeply perceptive meditation on the end of life, remarkable for a composer who was only in his forties.

Now I have this box, I wouldn’t want to be without it.

SM