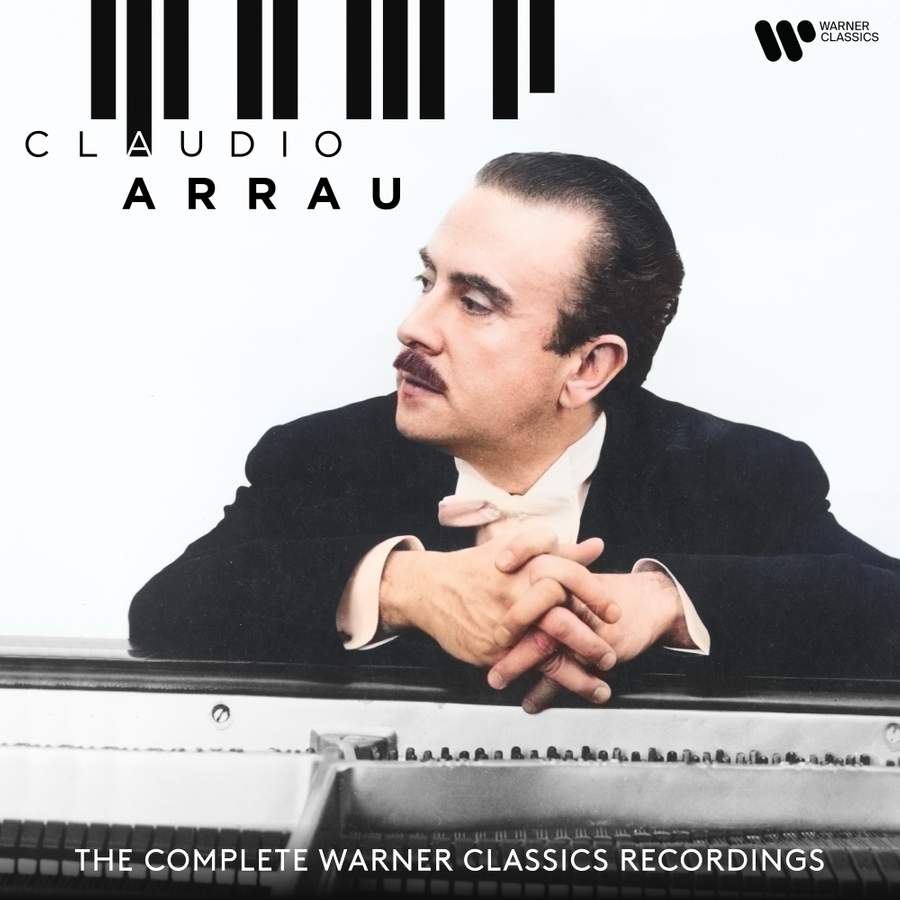

Claudio Arrau Piano

Philharmonia Orchestra

Carlo Maria Giulini, Otto Klemperer, Basil Cameron, Alceo Galliera Conductors

24 discs

Warner Classics 0190296245572

Budget price

The Review

“How great that you heard the Brahms at the FTH last week,” Sir Adrian Boult wrote to me on 12 December 1973. “It was such a great experience for all of us – I think he is the greatest of all pianists.” We were talking Claudio Arrau and the performance of Brahms Boult had conducted at the Free Trade Hall in Manchester (so 50 years ago later this year).

Arrau was then 70 and had more than a decade at the top to come, having already been recording for half a century. Boult (at 84) not so long, sadly.

Claudio Arrau was the most upright of Chilean gentlemen, serious in everything he did. By the time I heard him, he was thought of firmly as one of the clutch of superb pianists who had studied in Berlin during the First World War (he was only 15 when it ended), in his case with Martin Krause, one of Liszt’s pupils. His link back to the 19th century virtuosi was direct. In 1915 he actually played Liszt’s First Concerto in Dresden with Arthur Nikisch, with whom Boult studied informally three years before.

The title of this box is not quite accurate because Warner Classics did not exist when these recordings were made. They were produced between 1921 and 1962 for the various companies now in its stable – mainly HMV, Parlophone and Telefunken. CDs 1 to 5 cover the era of 78rpm records, the rest from LPs, so the majority are from the 1950s. Most of the sound is very historical indeed, with the result that the solo discs fare better than the orchestral ones. He is unlucky too that his main conductor collaborators, Klemperer and Giulini, while going for great grandeur also went for tempi that make hard work of the Beethoven, Brahms and Tchaikovsky concertos. To be fair, the Klemperer versions of the Beethoven were not studio recordings but ones privately taken from radio broadcasts in the Festival Hall in 1957 and now in the British Library. In Beethoven he was much more compelling in the 1958 complete concerto set made with the less famous Alceo Galliera, and in Brahms by Basil Cameron (though in that the 1947 orchestral sound, very early in the Philharmonia’s existence, is too aged to be of other than archival interest). The opening Allegro of the Beethoven Third Concerto in the Galliera set, crisp and lively, moving along but never rushed, is a real pleasure and captures the Arrau I remember hearing fifteen years later. He does take the Largo very slowly indeed, though, and it tests the orchestra’s bowing and breath control to the limit. These days it would be thought eccentrically ponderous.

It is true that in slow sections generally Arrau was very deliberate but this works effectively in the solo recordings when he achieves a wonderful sense of inner concentration, often before bursting out into a dramatic cascade, as in the opening of Beethoven’s Sonata 26, Les Adieux. He is often thought of as a Beethoven interpretor but his Chopin playing was also glorious, as in his 1960 recording of the B Minor Sonata. Without ever losing shape he makes the music flow in waves, articulating with the steeliness one would now expect from a piano of Chopin’s own period, but there is such give and take in his playing that the storms are never absurdly dramatic nor the lyricism over lush. There is something reassuringly grown-up about Arrau’s playing at whatever age – whether in the very rare performances from his mid twenties in Berlin or London forty years later.

This is an immensely rewarding box and fascinating too. It is not for the listener who only wants one recording of these works on their shelves but as a reference point for pianism through the middle years of the twentieth century it is of huge value. Of historical importance too is Jonathan Summers’ in depth and excellent essay in the booklet.

SM