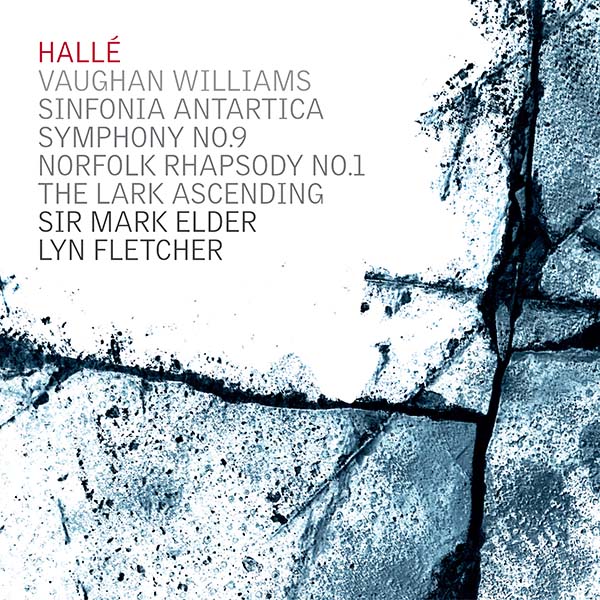

Symphony No. 7, Sinfonia Antartica

Symphony No. 9

Norfolk Rhapsody No.1

The Lark Ascending

Lyn Fletcher Violin

Sophie Bevan Soprano

The Hallé Choir

Hallé Orchestra

Sir Mark Elder Conductor

Hallé Records HLD7558

2 CDs

Full Price

The Review

If one wanted to illustrate the sheer scope of Vaughan Williams’ orchestral mastery, this set would be as good as any.

The Seventh Symphony might have been constructed from film music (Scott of the Antarctic, 1948) but the wordless female voices, wind machine and incisive wind writing hark back to the symphonic poems of Ravel and Debussy, Daphnis et Chloe and Images, even if the grandeur of the brass in the fifth movement march, Epilogue, has a touch of Respighi. The tautness of construction and the way themes are fleeting nods to late Sibelius too. At the age of 80, Vaughan Williams was still exploring, as much as the film’s subject, Robert Scott. By its nature film music is episodic but VW uses that sense of dislocation, as well as the relentless chill of the Antarctic, as a metaphor for the desolation of postwar Europe (Britain still had food rationing) and the new reality of nuclear cold war. This is the very opposite of the Festival of Britain. He was no fan of Conservative governments, wherever they ruled. It is telling that the 1953 premiere was not entrusted to London but to this orchestra in Manchester and Mark Elder’s predecessor (bar two), John Barbirolli. The dark modal progressions are chilling in every sense.

It is followed on disc 1 by the antithesis of landscape portrayal from half a century earlier, in the far more optimistic year 1906, a time when he spent his summers tramping around the countryside importuning locals to teach him folk-songs. The first of the three Norfolk Rhapsodies was written for the Proms and while its feeling of open skies and long views is palpable, barely a shower threatens, even if the solo viola theme is from the sad tale of The Captain’s Apprentice. That viola solo prefigures the glorious violin in The Lark Ascending, perhaps VW’s most untroubled (and therefore popular) work; the one in which pastoral content matches romantic longing. Written for Britain’s most brilliant violinist in the early part of the 20th century, Marie Hall (who had studied with Elgar when she was 10), it straddles the First World War – composed before but not premiered till after, by which time its innocent beauty seemed like agonised nostalgia.

She died in the months VW was writing his Ninth Symphony. The Hallé’s leader, Lyn Fletcher, does not try to invest it with every dollop of sentiment, is attentive to its magic but not tempted to indulge. The Ninth Symphony’s melancholy opening almost starts where the Seventh leaves off.

There is little Balearic sunshine, even if he composed some of it in Majorca, and it is elegiac, not only for himself in old age but for his friend Gerald Finzi, in whose Berkshire house other sections were written, close to that composer’s untimely death a few weeks before Marie Hall. I’ve always felt that Vaughan Williams treated this symphony, with its symbolic number, as a summary: referring back to the many variants of his style from the end of the 19th century onwards. There is the saxophone he used in his ballet Job, the hints of pastoral and folk song, ironic jauntiness, the monumental contrasted with extreme orchestral sparsity, the underlying struggle for visionary good to contain humanity’s thirst for destruction. It is not an easy symphony, which is probably why concert managers are still shy of it.

Above all, it needs (as does the Seventh) a conductor who understands how to maintain an architectural line across music that can feel disjointed and surprisingly nervy. There is nothing comfortable about the composer’s old age. This is ideal Mark Elder territory. He is a master at holding complex works together so that their development seems natural, however many strange turns the music takes. He is in his third decade with the Hallé and the orchestra’s stability is probably producing the same superlative quality that previous generations associated with Hans Richter and Barbirolli. This is England’s most intelligent conductor meeting the country’s greatest symphonist with its most consistently excellent orchestra: hard to better.

SM