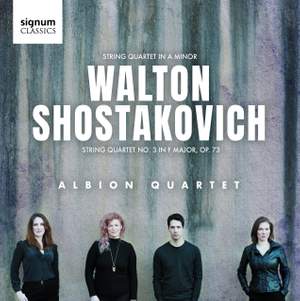

Walton

String Quartet in A Minor

Shostakovich

String Quartet No. 3 Op. 73

Albion Quartet

Signum Classics SIGCD727

Full price

The Review

There is a commitment and intensity to the playing on this disc that is, in my view, a real step forward from the Albion Quartet’s previous series of Dvorak quartets released over the last couple of years.

They find a veiled but sensuous sound in the long opening movement of the Walton that makes it hard to explain the work’s relative neglect. The pairing is an interesting one, comparing two quartets written by composers in 1946, the aftermath of war, when they were roughly the same age: Walton the elder by four years.

The second movement Presto and the final Allegro molto have bite, though not as sharp as would be necessary in the Shostakovich, but there is also a spring in its step which allows it to canter along without getting frenzied: nicely judged. The Albion are particularly good at slow movements – finding the lyrical heart without lapsing into sentimentality, which is precisely how to approach Walton. In the Lento the cellist Nathaniel Boyd and violist Ann Beilby are especially effective. Tamsin Waley-Cohen always knows how to make the violin sing and her partner at that desk, Emma Parker, finds a supportive hush which is beguiling. By the way, there are a lot of Parkers connected with this recording: Emma, producer and editor Nicholas, and sleeve-note writer Roger. Are they all related or is it just a random preponderance of Parkers?

The contrast between the two quartets cleverly shows the differing mind sets of the composers: both glad to put the war years behind them but Shostakovich still constrained, though not creatively suffocated, by Stalin’s regime. In makes me wonder what music will emerge over the coming years from Russian composers placed in much the same position by Putin. For Walton the following years meant marriage and moving away from kitchen sink England to build his own secluded fastness in Ischia. For Shostakovich there was nothing but survival to secure, at huge cost to his health

The Third Quartet is not as tortured throughout as some that followed, and the opening movement of the five is almost jaunty. The underlying cynicism at any frivolity is banished halfway through the second, though, and the Albion manage the change with chilling subtlety. When the third movement starts they are in full rage, attacking the notes with spite, unafraid to make a nasty noise when it is needed to drive home the point. The Adagio Fourth is a passacaglia labelled ‘homage to the dead’ but it also has the feel of a despairing love song, and the dialogue between the firm cello and the first violin, at one moment ethereal, at another fraught, is immaculately pointed by Boyd and Waley-Cohen.

All the elements of the quartet come together in the finale, interestingly almost exactly the same length as Walton’s ten minute opening movement. It is a summary and is hard to shape, the players needing to fashion the flow of music so that the different moods Shostakovich throws into it keep a sense of continuity without being diluted. A large pat on the back for the Albion in making this work so well – and Waley-Cohen plays the agonised lament that ends the quartet ends with tragic resignation.

SM